IForgeIron Blueprints

Copyright 2002 - 2008 IFORGEIRON, All rights reserved.

Hofi Interview

[An interview with Israeli blacksmith phenomenon, Uri Hofi]

The Golden Hammer

by Adrian Ioniţă

Reprinted with permission

Just as I was about to leave for Japan to continue my studies there, someone gave me Hofi's business card, so I hopped on my motorbike and rode out to his shop and spent a few hours talking to him. "You know", he said, after I informed him about my impending trip overseas "I know what you are looking for, but you will find it not in Japan or on the top of the Himalayas or the bottom of the ocean, but right here in my shop. I wish you luck!" After 12 years in Japan, after being apprenticed to a sword maker and a knife maker, after studying in numerous shops in Japan and United States, I know that he was right. The truth is often right next to you, but you have to walk an awfully long road to understand this.

[Arnon Kartmazov]

[© Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : Before we talk about your blacksmithing career, I’d like to start with a question about your name. Should I call you Uri, or Hofi?

Uri Hofi Let me tell you something, when I was a child in the kindergarten, were 5 boys with the name of Uri. To solve the dilemma, everybody was called by his family name. Since then, till now, everybody calls me Hofi.

Adrian Ioniţă: What means Uri in Hebrew?

Uri Hofi: Uri means light, “my light”, while Hofi means “my beach”. This is how you find out things in life. Ce mai faci, Adrian? (“How are you doing, Adrian?)

Adrian Ioniţă: This is unreal. Do you speak Romanian?

Uri Hofi: Before I joined Kibbutz Ein-Shemer in 1957, I came from a kibbutz where the founder was Romanian, so I picked up the language, you know, starting with, as always happens, bad words, like "F... D-zeii mă-tii"…but then, I was exposed also to the good things related to the Romanian language and culture, like the wonderful Romanian music and art. I consider Brâncuşi one of the finest sculptors of the last century. Of course, I won’t forget, the Romanian “mămăligă” and the pickled red watermelons.

Adrian Ioniţă: It is good to hear that Brâncuşi was Romanian; still, there are people who believe that he was a French artist. Please tell me something about Ein-Shemer.

Uri Hofi: Ein-Shemer is a half way between Haifa and Tel- Aviv. In the kibbutz the population is around 700 people, we have 1550 acres of land, we have avocado and oranges plantation, cotton wheat and maze fields, rubber and plastic injection molding factories and we all live in a communal life system. It is the place where I founded in 1988 The Hofi Forge School. It is a big school, equipped with eleven stations and since its inauguration I had more than 2200 students who followed the courses, many of them coming here, from countries with a strong tradition in blacksmithing. Counting the great interest and attendance during the years, I can say that The Hofi Forge School in Ein-Shemer is one of the largest private schools in the world. I make this distinction because there are also some other great schools, especially in community colleges in United States or occupational or trade schools in Germany where they teach traditional blacksmithing.

[uri Hofi with the family @ Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : Please, tell me something about your family and the tradition of blacksmithing in Israel at the time when you founded the school.

Uri Hofi: My father was a stonemason. During the years, I did a lot of things, pottery, ceramic, stone masonry and sculpture, tool making, working with leather, jewelry, shoes, my children worn the shoes I made… I have three children and four grandchildren. In older times, every village in Israel had a blacksmithing shop because it was the place where agricultural machineries were repaired, but when I joined Kibbutz Ein-Shemer, they had no blacksmithing at all. For 17 years I was in charge with all the field activities related to agricultural work, and managing director of three factories, a rubber, plastic and magnet factory. I started blacksmithing when I was 53 and now I am 73 years old.

Adrian Ioniţă: This is amazing, here is a 73 years old blacksmith who is considered by many, one of the most innovative minds of the contemporary blacksmithing, responsible of bringing back to life the passion for an almost extinct craft, and he is a Jew? The general perception about Jewish people is that they exceed mostly in the art of law and finances, are brilliant doctors, actors or writers, but blacksmiths?

Uri Hofi: Adrian, I have to tell you something. The Jewish people are competing in any field. It is in our nature. For instance, one of the most important figures in the American blacksmithing history was a fellow by the name of Samuel Yellin. He was a Jew. Yellin was a master blacksmith from Philadelphia and his art is considered a climax at the beginning of the 20th-century wrought iron design in America. Even though he died young, when he was 43 years old, he managed to do the largest forging company in the world. Only in one project, the ''Federal Reserve Bank'' from downtown New York, he forged in his smithy 625 tones of steel, the biggest forging work in the world in the modern time. In his smithy he had 60 forges and more than 270 workers. All the ironwork at the Federal Reserve Bank, the lower part of the tower, the window grates, the doors, the lamps, everything was done in his smithy. His granddaughter was till a year ago the president of A.B.A.N.A. There are many Jewish artisans throughout history, not only doctors, lawyers or professors.

Adrian Ioniţă: Before the interview, I did a research about you and I found out that you worked for a while in South Africa.

Uri Hofi: This is a long story but I will make it short. I built for more then ten years agricultural machinery at Ein-Shemer. Then I moved to South Africa, were I managed and developed agricultural farms, a real turning point in my life, no wonder that I returned three times to Africa and with one occasion, between 1984 and 1985 I founded and managed The Mabatoo Art School from Bophuthatswana. It was also the time when I studied history at the Tel-Aviv University and art at the Tel-Hai Institute.

Adrian Ioniţă: You traveled a lot and it seems that teaching is an important part of your life.

Uri Hofi: Within, two or three years from the day I decided to become a blacksmith, I opened a school, I developed the Hofi forging system, the Hofi Hammer, the free form forging with the air hammer, the crown and combination dies, I co-founded and start teaching in several schools of blacksmithing in the United States, at The Ozark School of Blacksmithing in Missouri, The Center for Metal Arts in Florida, New York, The School of the Big Blue, from Morganton, North Carolina, and currently I am opening a school in Portland Oregon. I’ll add to these, my participation to over 16 international conferences, I did several demonstrations at A.B.A.N.A conferences in USA, also in Germany, Italy, England, Holland, Japan, I spent even a month in Mongolia. Teaching became a central part of my activity. The reason for that is my realization of the fact that passing the knowledge to the future generation is highly important and has to be done fast, before we loose any traces of it. For me art means teaching and transferring ideas from one’s mind to another. Not only to preserve the culture. To see the smile on the face of my students, that is my reward. And I love it!!!!!!!!!!

[Workshop @ Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : To reinvent yourself at age 53 and become in such a short time an artist recognized internationally is quite a great accomplishment. Which are the sources of your inspiration ?

Uri Hofi: I am the type of person who learns all the time, from the most unexpected sources, but I can say without any doubts that Freddy Habermann triggered my passion for blacksmithing. Freddy, who unfortunately died in April this year, was a terrific blacksmith from the communist Czechoslovakia, and had a memorable demonstration at the 1984 A.B.A.N.A conference, where I met him for the first time. Since I was the only German speaking person at the conference, and Freddy needed a translator, he asked me to assist him during the demonstration, even though I was not a blacksmith at that time. It was a moment when I came to the realization and comprehension that something essential and meaningfull came into my life and I decided to become a blacksmith. It was a very surrealistic moment in my life.

Adrian Ioniţă: You mentioned the word "Hofi System", would you please, tell me something about it?

Uri Hofi: On Iforgeiron.com it’s a section called “blueprints”, where are presented over fifty lectures of mine. I have also many videos on DVD, and some of them can be found free on You Tube To put it short, the system is about ergonomics and not only that. A blacksmith is swinging a hammer several thousand times a day. Is hard on the body. Most of the blacksmiths have problems with their back, the elbows, the wrist, and this is caused by the fact that they hold the hammer wrong. When you raise the hammer, you bring the wrist joint to its limit and you damage it, but if you hold the hammer the right way, with the palm of the hand parallel to the anvil face, there is no limit to the joint and therefore no damage is done. But is not only that; my hammer is carefully designed and balanced. I use to say to my students: "I am not holding my hammer, I am guiding it"… For this reason, my system was named by many, “the karate system” of modern blacksmithing. To move it up or down, we use the internal forces, the internal energies of the hammer. Through the Hofi System, the process of forging becomes easy, you are not getting tired, and you do not damage your body. It is all about simplicity, safety, speed, and fun.

Adrian Ioniţă: How came these ideas to your mind?

Uri Hofi: By pure observation. And learning about the human body, physics, the laws of Archimedes and Newton, and so forth. I didn’t make anything new; all the information was out there for the past 2500 years. I have seen many craftsmen doing the same mistake just because they were taught that it is the only way to do it. Well, here I may repeat myself by telling how important it is to pass the knowledge as accurate as you can, but in the meantime, you have to think out of the box, all the time!!!!!!!! Not to follow blindly. Blacksmithing is very traditional. The British are working in one way, the French are having their way, the same with the Germans, and so on, and so on. But I am not coming from there, I am coming from another place and I am thinking differently. Therefore, I am asking two questions: one, “Why are we doing it this way? “ and second, “Can we do it better?” and always at the end, I ask myself one more time, “Can we do it better?” Improvement is a permanent way of thinking. People don't like to question too much, and somebody may say “If it was good enough for my father, than it is good enough for me” In 1994, at a conference in England, a fellow from the audience told me, “Mr Hofi, I am the son of a blacksmith, my grandfather was a blacksmith, 6 generations in my family where blacksmiths, but I never had a lecture about the hammer”. I looked in his eyes and I said, “ Yes, because you was born with the hammer of your father, and the hammer was passed from generation to generation and nobody came up with the question, why we use the hammer, why we use it this way? … You took it for granted and that is the definition of the Tradition”.

Adrian Ioniţă: Lets say that one day somebody will pick up your hammer and will say, “this hammer can be done differently” , what would you say?

Uri Hofi: Don’t get me wrong, I have a strong traditional upbringing in the trade; in the meantime, I question the tradition to a point where many can say that I am an anti-traditionalist. But I am not! Today we have a completely different deal, completely different steel, tools, completely different understanding of our body. I am an agent of change, and I want to see the process of change to go on. One day I was working in my smithy with 5 students and we had a problem. I never told them “Do it this way, or that way, or another way.” What I told them was “Tomorrow we will speak about it; I want everyone of you to come with his own solution.” 95 % of the time my solution works better, but one of my students had a better solution and I accepted it. I love it! If a student is coming one day, and tells me that he invented a new and better hammer I kiss him. But wait, these days I am experimenting with a complete new hammer, with a better balance. Also, I designed an anvil and a gas forge, which I’m selling through my smithy. As I told you, I never stop asking, “Can we do it better?”

[ball forming © Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : What means for Uri Hofi to be an artisan ?

Uri Hofi: You know the story of Israel when they left Egypt and they were 40 years in the desert? God came to Moses and said “You have to find somebody, its time for us to build a holy place and the Covenant, you have to find somebody with the wisdom of the heart.” What does this mean? This man has to be a wise man, he must understand, he must know, and love, and must be able to plan ahead. He also needs another quality. He must to be an artist. But on the top of all his qualities he has to think while he is working. The Hebrew language sums this better than other languages - “To have the knowledge of thinking and working together.” The name of the chosen artisan was Bezaleel. He made also the Menorah, the symbol of ancient Israel. It was done by beating a single bar of pure gold. He did not cast it, did not use files or chisels, he did it with a hammer. That means to be an Artisan!

Adrian Ioniţă: The hammer, obviously is one of the most important tools of the blacksmith. Please tell me something about the way you use it, or handle it.

Uri Hofi: When you forge is not only the power, many people are dealing with the power, but is not the power, it’s the rhythm, the music, speed=velocity, the internal energy, the using and the saving of the energy, and all these things together. The result can be seen in the form. The right rhythm will give the right form. Between rhythm and form it is a very subtle but direct connection. Working too much may spell disaster for form, too little will give you something blank and unfinished. When I am doing a leaf for example, I am counting all the time. Every leaf I am doing is done with the same amount of hits. I am counting them. The form, the rhythm and the time are actually one thing, which cannot be separated. All of these are also connected with the amount of energy invested in producing a certain form. If all of the three things mentioned above are right, then the amount of energy invested for it is the minimum necessary for producing the form.

[The Hofi Hammer © Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : Is true that you taught blacksmithing in prisons ?

Uri Hofi: Stories are life. It’s why I was honored with The Order of Excelence of the German Republic, from the president Horst Kohler. While teaching in Berlin, I had this idea to teach in prison, not in a juvenile prison, but in a place where are kept some of the worst criminals. So, we built together with Martin Ziegler from Berlin a smithy in the prison, and I gave a class for five days. The program I initiated was extremely successful and from occupational point of view, it set into motion a proposal for a compulsory program of blacksmithing in all the prisons from Germany. In October this year, I will teach again and they will make a 45 minutes documentary movie about the program.

Adrian Ioniţă: I believe that working with a guy who killed his mother or girlfriend or a stranger, is not easy. How would you transmit compassion, love and hope in such a person?

Uri Hofi: You are right, is not easy. But I am not the judge. I am not God. I accept the people for what they are. They made a mistake. Something happened to them. Some of them were neo-nazi. For me like a Jew to meet nazi people of the modern era, was a challenging experience. One of them approached me and said, “ You are a Jew?” I said “Yes, why do you think that I am not a Jew? And he said, “This can not be, Jews look different, different noses, different ears, they look different.” Till today, not only in Germany, but also all over the world, anti-Semitism is alive. This does not mean that there is no hope. One day, while teaching in Berlin I met a young gentleman around 30, who attended my class. At the end of the class, we always sit together and have a closer conversation about the system, the content of the course, or future projects. Suddenly I see that this man has tears in his eyes, that he is weeping, and I asked him “What happened to you?” He was in the front of the other students and told us his story: “I live together with my parents. One day I told them that I want to study blacksmithing and go to Berlin. Why Berlin? my parents asked. Because I heard about a very special teacher, and I want to study his system. Who is this teacher? And I said that is a fellow from Israel. A Jew, are you going to learn from a Jew? Not in our family!” Then he continued his story and said that his parents are till today members of the Nazi Party. The swastika is hanging on the wall in their house and his grandfather was a former member of the Gestapo. Despite his parents’ resistance, he came to the class and that is a sign of change and hope.

Adrian Ioniţă: A real emotional story. It seems to me that blacksmithing became for you a matter of education in craftsmanship, but also a vehicle for a better understanding of the human spirit and the problems we face today in the world. I know that in Israel are also many changes and a strugle for peace with the Palestinians.

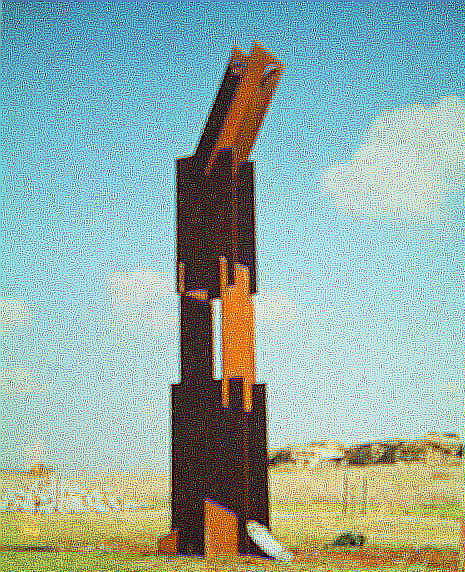

Uri Hofi: I am glad you mentioned that.In my school in Israel many Palestinians are coming to study with me and is no problem at all. I am the author of a monument commissioned by the peace movement with the Palestinians. The monument is 9,5 meters tall, and weights 7.5 tons. It was built out of heavy plates of steel incorporated one in another in a very special way, so that if you look at it from the side, resembles praying hands. Praying for God and praying for peace. The idea of the sculpture was inspired by the way children are building palaces from playing cards, by building them one upon the other, and they always fell down.The same thing it happening with the peace. To make peace you have to make it from something solid and strong like steel. There are 2 plates; one is the Palestinian plate, the other the Israeli plate. Each plate has a little mark with their flag. Why? Because each one is a nation. You can not melt nations, but that does not mean that you can not forge them together to live in peace.

[Monument for Peace © Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : It is what we all hope. Only peace can bring happiness and freedom in the world. Hofi, tell me something about your objects. I have seen on your website a beautiful bowl made from a thin sheet of metal.

Uri Hofi: You are not the only one who likes that piece. It won a 1st price in Italy, at StIA. One piece, no welding, just forging. I love simplicity. It’s so much power in humbleness. Moreover, is not easy to do it. Believe me. To make simple things is complicated. I feel repugnancy for pompous things. At Iforgeiron.com it is a Gallery where are over 500 entries with my works. Many people asked me to put my objects in the galleries, in Tel Aviv, or Jerusalem, but I refused.

[Wall sculpture © Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : Why?

Uri Hofi: In the past I had several exhibitions in the galleries. One of them which opened in Tel Aviv had the name “ Tools as sculptures and sculptures as tools” The galleries are in a sense commercial places, a kind of business which exposes the artworks in a cheating light compared to the authentic circumstances in which are born. This does not mean that there are not fine galleries around, but for now I prefer to stay as closer I can to my work. A show which was dear to me, because was related to Chillida, an artist I always admired, was opened in 2oo2 at Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin and was integrated with what happened to be Chillida’s last show, because he died that year. Out of all the blacksmiths in the world they selected me to show the tools of the trade, and that meant something to me.

[sculpture dedicated to Tonni Benneton © Uri Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : I have to agree with you that sometimes, what we see in galeries or museums can be deceiving.

Uri Hofi: By the way, I read your article about Past -Future -Imagism where you describe the reaction of the art criticism about Duchamp's ready-mades. I do not think that it is important whether Duchamp had made the object himself or he found it in the alley and raised it on a pedestal in a show. It makes no difference, it is just BS. The reality of the object speaks for itself beyond the stories surrounding it. Duchamp made a declaration of art, a statement. Picasso's "Tete de Toro" which was completed by him in 1943 putting together bicycle parts is one of the most beautiful sculptures in the world. This unexpected dimension open to free interpretation is what makes me happy, even if I do not know anything about the making of the object. The same thing happens when somebody is writing a song, and somebody else is trying to explain the story of the song, its meaning, or philosophy. What is important is what stays with us, and that is the song itself. There are so many layers, and if we go and dig and dig and dig, and at the end we dig too much, we loose the fun of looking with real eyes to a piece of art and say, “This is fantastic!”. For instance Picasso did 324 sketches for his "The Three Graces" and eventually finished his painting differently. Regarding these sketches and their history, we can talk as long as we want, but what is important is the end result.

Adrian Ioniţă:How do you develop your artwork, do you make sketches?

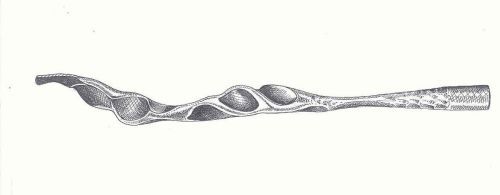

Uri Hofi: Rarely. Usually I develop a design or strategy, mentally. I don't do anything before I finish my thinking. Sometimes I am thinking about an idea for 2 years and afterwards, when the idea is finished in my mind I can do it in 20 minutes. Talking about sketches, Sahar (moon in Hebrew) Hofi, my 20 years old granddaughter, a talented aspiring blacksmith, did the illustrations for my recent book about blacksmithing, published by Johannes Angele in Germany.

[drawing by Sahar Hofi © Sahar Hofi]

Adrian Ioniţă : Before we wrap up our interview, I know that you are very busy, please tell me something about your future plans.

Uri Hofi: Several years ago I traveled to Japan and I had a great experience in Sakai city, near Osaka. Sakai is an industrial city where are active over 540 blade makers and where Ashi Hiroshi a famous Japanese master blacksmith invited me to present the Hofi system. I intend to go back to Japan, this time for a longer period, and study Mokume-Gane, a Damascus technique formed with layers of cooper silver and other metals fused together through heat and pressure. In October I will be again for a demonstration and a documentary film in Germany, also I will travel to Holland, and United States were I have several courses in general blacksmithing and the Hofi system, and in general to go on teaching and improving the forms and the techniques as long as I can!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Adrian Ioniţă: Dear Hofi, thank you very much for the interview.

[bowl, winner of the 1st prize at StIA © Uri Hofi]

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.