-

Posts

129 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Articles

Gallery

Downloads

Events

Everything posted by SnailForge

-

52100 is wonderful stuff. Just not for razors. A2 and D2 are not used for razors. O1 and W1 are. Of the 2 I would go for O1 because It won't warp whereas W1 is a bit trickier and it can be discouraging to have your first razors go PING. A guy I know destroyed half the things he made in 1095.

-

This is going to be an article on how to make a razor. There are many ways to go about this. Some people will do it differently. Some makers whose work I respect a lot work differently. This is just how I work, and it works for me. At a high level, it goes something like this: I start with stock, and forge a razor blank to shape. I anneal it, grind / file it to shape, and do heat treatment. Then comes the finish grinding, polishing, and making scales. At that point it is ready for honing and test shaving. During the process, I don’t use center lines, I don’t measure angles, and with a couple of specific exceptions, I don’t measure anything. It’s all eyeballing and ‘that looks about right’ engineering. In this article, I will work on the assumption that if you want to follow it, you already know basic forging, metal working and heat treatment. I will post this article as separate posts in this thread, so that I can write pieces as the razor in this article progresses. Steel I will use Damascus for this project. It should go without saying that you should work with materials that are suitable, and that you are confident in working. A razor can be a tricky thing to make correctly in terms of geometry. Before you move on to expensive materials, you will want to be confident in your skills, know how to recover from mistakes, and have enough experience to recognize the first signs that things are about to go pear shaped so that you can correct in time. A good steel for razors should have enough carbon (0.7% or up), have a fine grain, and be free from many of the alloys used in knife steels. The only requirements for a razor steel are that it can take a fine edge and be honed by a human. A razors edge is not subject to shearing forces or impact. It does not need to be wear resistant. That means that 52100, M42, Hitachi blue steel, while excellent knife steels are not good choices for a razor. They are extremely difficult to work, especially the post heat treatment grinding and polishing. They fight you every step of the way. When get to the honing stage, it will be a dog to hone because it is so wear resistant it is like whittling down your stones. And in the end, the edge will probably not be as fine as if you chose plain carbon steel. Then there is oil vs water. A hollow ground razor can easily crack or warp during water quenching if the hollows on both sides are not identical. And even then, it may crack if it hardens differentially. And because of the thickness of the spine, that can happen. With oil that is usually far less an issue. When it comes to regular steel, my preference is O2. It is in my opinion the best steel for a razor. It has .95% carbon, Manganese which makes it harden nicely, and nothing much else. It also produces edges that are fine, strong, smooth, and yet pretty easy to hone. It is not available in the US anymore, so we usually tell beginners to use O1 instead because it is a pretty good general purpose steel. The Tungsten makes it fight a bit harder than is ideal, but the heat treatment is straight forward, and quenching is safe. In this case the Damascus I use is an O2/L6 mix which is made for me by Howard Clark. Howard makes it for me without precision grinding it. It would be pointless for him to precision grind it only for me to throw it in the fire and hit it with a hammer. It might look like precision ground stock in the pic, but that is only because he is just that good with a power hammer. The first thing I do is grind the sides clean to double check there are no welding issues, and to grind away any evidence of the last fold. It’s been my experience that if you get rid of the lines that show the last time it was folded, the odds of it splitting when I hammer it are drastically reduced.

-

Actually I am of the opinion that a heavy hammer is better. Because a light hammer lets you get away with sloppy technique which will need to be un-learned at some point, in terms of ergonomics. A heavier hammer will tell you very quickly that you're using it wrong. What also helps is someone who can tell you how to use it. Last weekend an ABS mastersmith explained me how to properly use my new 3.5 pound hammer. I can now move metal twice as fast and I can hammer for 2 hours without getting tired in my arm.

-

I have not seen much leaf spring around here, but when I started out, I used old files. Over here you can find those at any garage sale because there are always a couple of guys selling rusty old tool boxes where you can often buy rusted Nicholson files for a dollar. Once you have some experience, switching to good stock is not going to be much more expensive.

-

Height of bench for a belt grinder

SnailForge replied to LawnJockey's topic in Grinders, Sanders, etc

Whatever height is comfortable for you. Mine are at a height where I can use them while sitting on a chair, because razor grinding can take a lot of time and I don't want to keep standing and stress my back. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

I admit though, that I am in the comfortable situation that I don't need income. I make good money from my razors, and I just spend it all again on equipment and more steel. I have the luxury that I can take my time and the luck that people like my designs. In fact, several friends of mine are professional high end knife makers, and many of them have stopped taking orders altogether. They make the things they want to make and then just sell them. Occasionally they do take orders, and then the client pays a mint. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

That is a good approach if you are interested in making many of the same thing, or if you need to make sales. However, I seek projects based around what I would like to make, or follow up on design ideas. The first one is usually the most interesting. I sometimes make more than one of the same if requested, in which case that person will pay for my shop time. Some people make a business of selling cost effective razors. Some of them even succeed. Good for them. But me, I just prefer to chase design ideas, work with interesting types of steel, and have fun while charging prices that approach 4 figures. I sell everything I make and usually it is gone very quickly, so this approach is working for me. If I wanted to go cost effective, I would need to focus on tool teel, and squeezing every minute from my process. I'd much rather work with Damascus, Wootz and tamahagane to name a few. Once you go into that territory, collectors and aficionados are who you are marketing at, and they could generally care less about cost. they want something unique. They want sizzle with their steak. Not just nutritional value. -

I sent a PM because I do not know if it would be against forum policy to talk about prices in the forum.

-

It's also a good idea to wear a full face shield if you're breaking a knife. I once had a shard zinging through the workshop when I broke a knife. Since then I always wear a face shield if I am breaking stuff.

-

It'll be a multi part how to for sure. The first one has a couple thousand words. I still need to add in some pictures. Problem is I can't do such things half assed, so it will be lengthy and wordy

-

Thanks. The first installment will hopefully be up this week. The first one will talk about steel, geometry, some background on razors and their users, and the layout of the other installments.

-

How I calculate knife prices

SnailForge replied to j.w.s.'s topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

Yes, your price per hour is quite low. I calculates shop time as the time I am actually doing something, so I would not count the HT. But I would count a higher price per hour. My plumber is not working at 15$ per hour, nor is my electrician or anyone else who ever came by my house to do work. I see no reason why I should charge just 25% of what a plumber earns. And that is WITHOUT the cost of materials. That knife is definitely worth more than what you asked for it, and if you have to live off of that, you probably have no cushion at all. Especially considering that that amount still needs to be taxed with VAT and income tax. If, as you say, you can put 310 paid hours in 60 actual hours, then it means that your timekeeping is completely wrong, and your actual price per hour is much higher and the 12$ is just a nonsensical number and you are actually closer to 50 - 60$ per hour of actual labour, which is also where I am at. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

Rockstar, what you are saying is not wrong. It is how I got started, when I still had to develop a number of skills and my work was basic. However, a couple of thoughts. I have a good reputation and deliver quality work. I produce items for a luxury market, and I charge more or less market rates for my work. Slightly less actually, but I need a couple more years before my reputation is up there with the big names. I already make as much razors as I have the time to make, at the prices I charge for shop time. I don't see a reason why I should price my razors at lower prices when I am already constrained by how much razors I can make. I work the opposite way to what you describe. Market prices more or less determine my prices. I don't look for stuff to add, I look for ways to be more efficient at making things so that the amount of time needed decreases. The end result of that is a higher price per hour for the same razor at the same price. For typical work, market rates now satisfy my shop time rates. What you describe is indeed how I started initially when I first sold the fruits of my hobby. I've done that a couple of years; working my way into the market from the bottom. But that is not the point where starting a business is healthy because the overhead will kill you. Once you have established a reputation, you should be able to get market prices or better, and keep an eye on the bottom line. Especially for the things you make routinely. I still take on projects where I don't make my shop rates, if the work is interesting enough or when it can be used to increase my portfolio -

Heat treat HEAVY knife (leaf spring)

SnailForge replied to Urthman's topic in Heat Treating Knives, Blades etc

Even so, I would NEVER use scrap steel for anything that will be subjected to severe impact or high tension. Even if you just give it away and they use it for 'kicks', it is just too dangerous. Truck leaf spring can have hairline cracks internally or fatigue places. If they try to force open a door just for laughs, and the bar breaks under tension, someone can lose an eye or worse. It is cool that you want to give it away, and if you want to do that, start with known good steel that you know how to heat treat. For a knife it wouldn't matter, for an impact tool or prying tool it does. Of the steel I have worked with, I would probably choose 52100 for the usage you described. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

Well, my charcoal fire is in the garden where I built a semi-open smithy. The basement is where my grinders, drill press, bandsaw, etc all are. Forging in a place without ventilation didn't seem like a good idea. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

Probably not. I don't know if you are registered as a business or not, or whether this is required for you or not. If it is, then you're not even making 2.5$ per hour. Now, that said, when you are still in a the learning and experimenting phase, it is normal to work at cost or just slightly above. The reason is you have no reputation yet, still need a lot of time, and still need to scrap a project now and then. My first razors all went at cost, at very low prices. In fact, I sold all of my early work unfinished, meaning they were heat treated and ground till final shape, but not polished or fitted with scales. This way I could do more of the difficult and fun work in the same amount of time. And since enough people were interested in a custom razor without paying full price, I sold them all. I guess this is what you'd call a kit knife in the knife world. The price per hour only becomes important when you have your process down and are selling things as part of a normal routine. Experiments and learning projects can be done at cost. Track your times, and see where you can optimize. Also, people tend to focus too much on the cost of equipment, and decide to make things themselves. My first grinder cost me 2000$. Many people make their own no weld grinders, and pay about 800$ in materials, so they go that route. I am lucky enough that my wife told me to just buy my first grinder (because I don't spend money on anything else) and since then I've noticed that it is often more profitable to buy quality equipment and make and sell a couple of knives / razors in the time I would otherwise have spent building said equipment. Electricity for the lighting, the welding, the tempering oven, the power drill, the grinders. Charcoal for forging Sanding paper for polishing Grinding belts for grinding Discs for an angle grinder. Flux Acid etc.... It is important to keep track of those, especially if you are running on low profit margins. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

You're right: forging does add some 'je ne sais quoi' to the steel. At least from a marketing point of view. That said, forging the blank to size makes a lot of sense for razors. Razors have a thick spine, a thin edge, and a tapered tang. I can hammer out a wedge shaped blank with a tang and tail in far less time than it would cost me to stock remove that awful lot of metal from a 1/4 thick piece of stock, which would also cost me a 40 grit belt. And if you work with expensive metals such as Damascus steel or suminagashi or wootz, the difference in required stock can have a substantial impact on the price. I know of 3 razors that were made in Pendray wootz by a stock remover. I cannot fault the quality of his work, that is functionally without a fault. But the fact that more than half the wootz ended in his grit bucket still makes me cringe. I could have made 3 razors from the whatever was ground away. Well, not after grinding of course, but there was enough stock for 6 razors instead of 3, if the blanks were forged to size. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

As to the financial side:I don't haggle. I calculate the price of a commissioned project up front, and I don't back down from that. It will cost what it will cost. If that is a problem, I will work with the customer to change the design or he materials to cut costs, but never ever do I lower the price without simplifying the design. That is just bad business, and tells your customer that you were overpricing to begin with. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

It is not complicated. every project consists of the same steps when you get down to it: forging, rough grinding, post HT grinding, polishing, making handles, sharpening. those columns are all in minutes. if a columns is not applicable, simply put a 0 then there are cost columns: steel, handle material, misc (pins etc), consumables (belts, charcoal in my case, etc) Then you have a column for the price, and in the results you have profit per hour, and total profit. total profit is price - sum of all cost columns profit per hour is total profit divided by the sum of the time columns converted to hours The sheet also contains customer details, date of sale, a unique order number, a link to the pic of the finished product, and a status of the order (waiting, in pogress, ready, paid, done, held, cancelled) From the very moment start a specific project, I make a slip of par on which I can write the number, and the paper goes in a small plastic box tha is large enough to hold the blank during each phase of the project, together with the scale material, pins, etc. That way everything stays together, and it is easy to store many projects without losing things.. This is also very easy forthenon commissioned projects. I regularly make razors according to my own design, and I stop after the heat treatment or finish grinding stage, and I just put the boxes away. That way I have a small stock of things to be finished upon customer request. -

I seem to be missing the critical temperature and quenching part in your explanation

-

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

Oh yes I forgot: about counting beans. For every single thing I make, I fill in a little report card I made myself. On that, I note down the cost of material, cost of handle material, cost of consumables (belts etc). And also the number of minutes on each step: forging, rough grinding, finish grinding, polishing, making scales, etc. All of that goes into a spreadsheet that takes those numbers an tells me how much I've made, and how much I've made per hour. This way I can identify the areas where I spend the most time, and optimize there. And it also allows me to make better estimates. After all, a fixed handle hammer finish razor is a lot faster to make than a suminagashi razor. But regardless of what I make, this way I can come up with a realistic price for each tpe of razor I make, after a couple of razors, so that I make the minimum amount per hour I have set for myself. This is after all a business. No matter how much I like this, a business has to be run by the numbers. I have set myself a minimum rate of dollars per hour. I am sure that many people would think that with that rate, I am getting rich. But those people have not thought about paying VAT, paying social security on the profit, and then giving the final pound of flesh to the IRS. If you can't gross 250 - 300$ per day, you might as well quit, because after paying all thos things I've mentioned, what remains is a whole lot less. -

Taking a hobby to a business

SnailForge replied to SnailForge's topic in The Business Side of Blacksmithing

I know badger and blade. I don't go there because I am administrator at straightrazorplace.com. There is bad blood between the respective owners of those 2 sites, and as admin this could cause problems. And for info on straight razor making, we have a lot more info and makers. We have a vast workshop and forge section dedicated to razor making. -

I am in the process of turning my bobby into a business. I thought I'd share my findings and experiences. My hobby is blade smithing, straight razors in particular. That's what I am making a business in. I still have a day job, though I am currently working 4/5, and 1/5 on my blades. Before I did this, things were pretty much the same, though I got less things done. Might be I will need to go 5/5 again, but then I can still do this in evenings and weekends. Starting of in the hobby phase is good, because I can re-invest all money I make into the shop. I don't rely on this money for making a living. Plus I get normal benefits at work through my day job. There is no risk to me. this means I can reinvest everything, and also take on interesting projects that may take more time that I anticipate. I registered as a business owner, and got myself an accountant. This costs money, but you get someone to give you qualified advice about what you can deduct as an expense, how to create invoices, and many other financial things. Formally registering as a business also has the advantage that you can register things as cost, and (partially) deduct personal costs you'd make anyway, such as e.g internet and other things. The accountant can also do my taxes better than I could do myself. I use facebook, twitter, a personal webpage, and participation in topical forums to put my work out there and to market my products. If people don't know me, they won't become customers. I also put some thought into which demographic I wanted to reach. I make functional works of art. This means I have to invest in design, and high quality standards. My prices are high, but then I also need a lot of time per item. This is not better or worse than other approaches, as long as you put some thought in where you want to go, how you can get there, and what this means for your business. One of the benefits I have is that I don't have to perform works via contract. I make something, I sell it, and I get the money in full before I ship it. My only issue is people backing out. This happens, though rarely. I never ask for an advance payment. People backing out is rare, and when it happens I can sell the item to other people without a problem. It also means that I can work as if I am beholden to no man. Another benefit is that I have no legal obligations, and I've found that especially in the more high end market, people with money, especially senior people in the communities I am part of, appreciate being taken as men of their word. In the blade world, you also have to build up a reputation and a brand name so to speak. This takes years. That is another reason why starting from a hobby and doing this as a limited part time business has the advantage. Initially you don't have long waiting lists and not always a lot of well paying projects. That doesn't matter, because you don't really need the money. You can do it for the enjoyment of the art. After several years, when you have a good rep, and a steady influx of projects, you can turn pro if you want, without a whole lot of unknowns. Because then you have customers, processes, suppliers, fans, a reputation, etc. You can switch from hobby to pro without a whole lot of risks and unknowns. That is more or less the plan I am following. I am in no rush. In 15 years time, my mortgage is paid and my kids out of college. By then we have far less costs than we have now, I will have a good view of how much I can earn on a monthly / yearly basis as a bladesmith, and we are in a place where we can deal with less month to month financial stability. In the meantime, I have a hobby that pays for itself and for some of my personal expenses.

-

Indeed. I thought about a collapsible design, but since this thing is holding my grinders, and they're not meant to be moved around, there was no point. Welding everything in place has the advantage of being rock sold and cutting down on the vibration. Btw, if your grinders are balanced properly, they shouldn't vibrate at all. Mine don't

-

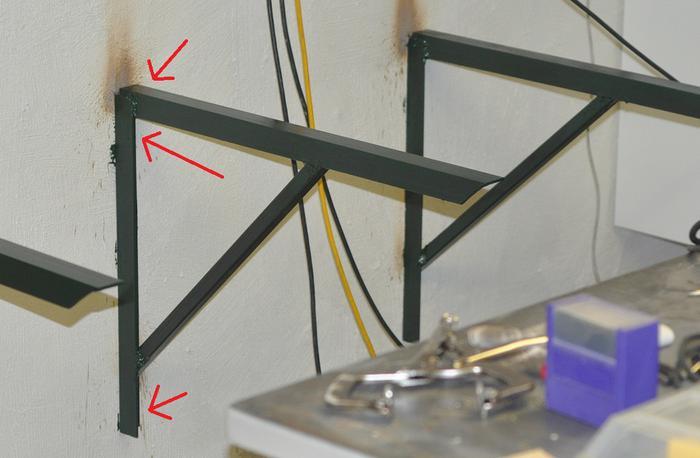

I came up with this in the process of overhauling my workshop, and the last big change is going to be throwing out the improvised wooden table that held my belt sander, and replace it with a sturdy workbench that will hold at least 2 of those grinders, and possibly 3 sometime in the future. anyway, aside from being sturdy, I wanted the thing to have no legs. The wall itself was not 100% flat, so that made it impossible to just buy wall hooks for supporting my workbench. They would not be level or equal. And most of the off-the-shelf stuff is not for for heavy loads anyway. So I bought a load of steel L beams, roughly 3/16" thick, 1.5" wide. First I mounted the vertical beams. Each of those is mounted to the wall with 3 bolts that are meant for hanging cast iron radiators from a wall (2 bolts will hold a 200 pound radiator easily). the position of the bolt is indicate by the red arrows. I placed 2 bolts at the top because that is where all the weight will pull. Then I welded on the first horizontal support, using a level indicator to make it perfectly level. I repeated this for the other 2 supports, using the first as a reference. After that I welded on the diagonal square beams. I'll not call it a professional welding job. It is basically just a frame that I melted together using welding rods. After that I coated everything in hammerite to protect it from rust. Each of those frames is perfectly level with the others, and is strong enough to hold my full body weight at the full extent of the horizontal support without moving. Now it is ready for the wooden cross beams and the table top