Alwin

Members-

Posts

188 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Articles

Gallery

Downloads

Events

Everything posted by Alwin

-

This website Lucian Avery - Smithing - Video - Forge Welding shows a method of upsetting a scarf that I like to use. It is fast and as you are upsetting you are also starting the scarf.

-

I have a power hammer which I use for heavy drawing out, but I still use my hand hammer a lot of the time. Drawing out 3/8 inch and smaller I'll often use my hand hammer and aggressive forging doesn't necessarily mean ragged or pitted. If your edges aren't too sharp for the force then it is just a matter of walking the steel you are pushing, kind of like a wave, from where you start to the end of where you're working. If you do that then there isn't much work to get a really smooth finish. I sometimes want a smooth finish, sometimes a rippled surface, and sometimes a more faceted finish, it depends on the project. I use mainly traditional techniques but I can't say I do a lot of traditional projects. I like hand forging steel (at least some of the time), I find it very soothing and when I am immersed in it the hammering gets to a point where it feels almost effortless. There are definitely many tools that lessen the amount of hand hammer work needed, but if you are a blacksmith you are always going to have to do some. I also think I understand some of the subtler ways in which steel moves from that more direct and slower interaction.

-

The edge of your hammer and of the anvil both make a lot of difference. Let us say you have a 3/16 inch radius on the edges of both your anvil and hammer, the angle you turn the hammer or hold the steel on the anvil edge is also going to change the effect of the blow; the smaller the area that the force of the blow is going through the more aggressive the fullering action. The fastest way to move steel that I've found (using a hand hammer) and one that is sustainable over a long period of time is using the outer edge of the hammer and swinging straight down to strike the steel right on the edge of the anvil. I am holding the steel pretty close to horizontal while swinging the hammer down upon it.

-

In my training I learned to loosely wrap my first two fingers around the handle while just cradling it with the other two. In a swing the hammer pivots from the two fingers and the thumb. That adds extra speed without a lot of wrist movement. The hammer just loosely moves in the hand while you guide it. I was taught that the shoulder was the main joint to use because it is the strongest and a natural hammer stroke should be very similar to the movement of your arm when you swing your hand starting from it hanging straight down next to your leg up to right beside your head. In a good hammer swing it should be hard to wear ear muffs because your hammer will knock them off. The wrist has always seemed like a weak joint. The repetitive movement of the wrist in the basketball dribbling style still causes damage such as carpal tunnel in my understanding. Correct me if I'm wrong about that.

-

Hofi, thank you, I look forward your post. Ian, what Jon Dhalmo said about grip and also about glancing blows makes sense to me. I probably use the edge of my hammer or the pein 75-90 percent of the time while forging. Basically, I use the edge except for the final smoothing and finishing heats. So, even the little bit of vibration that it looks like one would recieve would add up quickly over time.

-

I like the horn of the anvil for fullering if the anvil is heavy enough not to move when you are working on it, however I think the most efficient place to work on an anvil is always over the waist. I say that because of the way in which shock/vibration is transmitted through the anvil. You will get a little more effect and rebound working over the waist. The horn gives a gentle fullering action that works well. Slightly tipping the hammer and using the face will do the same thing with slightly less effort- at least that is the way I understand it. I have been smithing for ten years-4.5 yrs working for another smith and 5.5 years running my own business as a blacksmith mostly using traditional techniques- and I've studied a lot of different smith's techniques both in person and by video, I say this so you understand where I'm coming from. I learn new things and make mistakes all the time so please correct me if I am not understanding something correctly or if you have a different explanation.

-

I understand the benefits of pushing the metal slowly, but by using a convex face, if you are drawing the metal to a point for instance, aren't you constantly pushing the metal in a direction opposite the one you are wanting to consequently making more work for yourself? A wider pein with more rounded edges will stop the problem of cold shuts and also make the movement of the metal more controllable, and edges on the face of the hammer can be rounded to allow for slight to very aggressive pushing of the material depending on whether it is tilted a tiny bit or a lot.

-

Using the pein of the hammer is a good way to move steel quickly, but I was addressing an argument about using the face of the hammer on the edge of the anvil versus using the edge of the hammer. It was an argument from an ABANA magazine. I personally like the cross pein because I can stand with my hip against the anvil and have the edges of my hammer and anvil line up so I can draw steel out using the hammer and anvil edge, stretch it wide using the pein, and make tenons and other changes in steel size using the hammer and anvil alignment all from the same position.

-

There are a few things I want to discuss in regard to the Hofi technique. I have seen Hofi forge in person and on video so I do have some familiarity with the technique on which to base these questions. The first question concerns the grip. I have heard of it described as pinching the hammer with the thumb on the side, allowing the hammer to move unencumbered vertically. Since much of the technique requires forging with the edge of the hammer and since the handle is rectangular turning the hammer to use the edge means the thumb is in a place which absorbs vibration, all the more vibration if you're pinching the handle. My question is whether what I've described above is true and if not why isn't it? My second question concerns the use of the Hofi grip and the movement of the shoulder in heavy forging. In watching Hofi forge it seems when he is doing heavier work his grip changes. When using the shoulder for heavy blows a thumb grip on the side of the hammer handle with the hand remaining parallel to the anvil requires the shoulder to move out from the body which isn't the most efficient direction for the shoulder to move and limits the height to which the hammer can be raised. I am asking whether for heavy forging the grip changes and if not how the shoulder movement works with the Hofi technique? If any of these questions don't make sense I am happy to clarify. I am hoping to get pictures posted soon, and when I gain that ability I will try to illustrate the points I'm making. I want to make sure that I am not seen as someone attacking Hofi, that is not my intention. I am just looking for a rational discussion to understand that which I don't. Furthermore, I admire Hofi and think he has contributed many wonderful things and tons of great information to blacksmithing.

-

I will preface this by saying that this thread is brought up to increase understanding. I recently read through a number of recent articles in the Hammers Blow magazine. There was a debate about using the edge of the hammer to draw out steel versus using flat blows and the edge of the anvil to stretch steel quickly. I am a practitioner of the edge of hammer technique (in conjunction with the edge of the anvil when I want to stretch metal very quickly) and the body mechanics of flat blows using the edge of the anvil have always seemed inefficient and awkward to me- not that my impression is true. I generally see people standing with the anvil in front of them the horn facing either left or right to them while they hold the steel and use the far edge of the anvil to hammer on. Anytime I've seen anyone doing this they've been swinging the hammer at an angle which requires more physical effort and limits the effect of gravity compared to a straight up and down blow. Holding the steel facing out in the same direction as you're hammering makes it much harder to stand over the work which means that your hammer blow is going diagonally towards the steel and diagonally back to you, all of the diagonal direction has to be created by your body. Unless the material that is being worked is too long to be held at a 90 degree angle to your hammer swing, working at the anvil in that way seems more inefficient. Using the edge of the hammer and standing so you face down the length of the anvil makes it so you are standing over the work which creates a hammer blow closer to straight up and down. I might also argue that using the edge of the hammer makes it easier to control the degree to which you're stretching the metal because the effect is seen on the top of the steel being struck versus on the bottom while using the edge of the anvil. There are fantastic blacksmiths using all sorts of techniques so pointing out someone who does great work with a certain technique has never seemed a good argument for using it. Pointing to a blacksmith who has used a technique for a long time without injury is a better argument but still doesn't speak to whether the technique moves steel in as controlled and rapid a way as possible. I think that a systematic look at the way the body moves in relation to the joints and gravity is what it comes down to. I agree with Hofi in many of the fundamentals but I have a few questions regarding his technique- once again not saying that any of it is wrong, just that I don't understand it- that I will address in the next thread.

-

Recommendations for an beginner's hammer(s) & tong(s)?

Alwin replied to Barnaby's topic in Blacksmithing, General Discussion

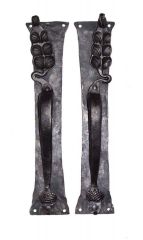

I would recommend starting with a hammer with a short distance from the eye to the face, and not much longer from the eye to the pein. A hammer in which you can turn the face at a 35 to 45 degree angle to the anvil face and still have the eye over the edge of the hammer will serve you very well. When you hit with the flat of the hammer the metal is driven in all directions which means that if you want to make a long taper you are constantly fighting against yourself. By using the edges of the hammer you are able to focus the movement of the metal in just two directions. When using the edge of the hammer you aren't swinging at an angle, you are still swinging straight down. If the eye of the hammer isn't directly over the part of the hammer hitting the steel the whole hammer will want to roll over. I remember Elmer Roush telling me that when he was learning techniques in Czechoslovakia the instructor would put a dab of paint on the center of the face of the hammer and want that paint to still be there at the end of the day; the idea is that by using the edges of the hammer you will learn to control the directional movement of metal much faster- it also requires less work to make the metal move much farther which is very encouraging. Look at Hofi's instructions on moving metal he will give you great insight. I would disagree with some of the other's postings and recommend (if you are really serious) to get a good hammer such as a Hofi hammer, an Elmer Roush hammer, Blacksmith Depot's german short hammer, or a Habermann hammer- I've only seen pictures but it looks like it would be a good one. Starting with good tools and good techniques will make it easier, more fun, and less damaging. -

One way I like to make leaves is by spreading out a wide leaf shape with the pein of the hammer. Then I use the anvil step or a swage block to bend the leaf in half lengthwise. I hammer the crease and then use the hardy to open the leaf. It gives a leaf with a very deep center vein and makes it a very 3 dimensional leaf. I also like leaves which have been decorated with punches, the ones in Otto Schmirler's watercolor blacksmithing book are great examples of that style. I often make oak leaves in that style. Frequently, I make leaves just using the pein of the hammer (my pein is similar to the ones on the Hofi hammers). As I stretch the metal with the pein to form the leaf shape I turn the leaf so that the pein comes down on half the leaf at one angle and on the other half at another angle. The finished result is that the texture of the stretched out leaf suggests the veining of the leaf. It is hard to chisel veins into a leaf without having the result look like the factory made ones welded onto items in Lowes and Home Depot, though it can be done.

-

You want the thicker piece in a slightly hotter part of the fire, and when you get to the anvil you'll want the thicker piece to be the one in contact with it. With experimentation the two pieces will get to welding heat at the same time. I often find that putting the thinner piece on top of the thicker one while slowly heating them in the fire until they are close to welding heat and then bringing them side by side works well.